This is an expository essay I wrote for my human development course in UP College of Education as a requirement. Feel free to cite this work or the references I quoted in this piece. It is a lengthy essay though.

Introduction

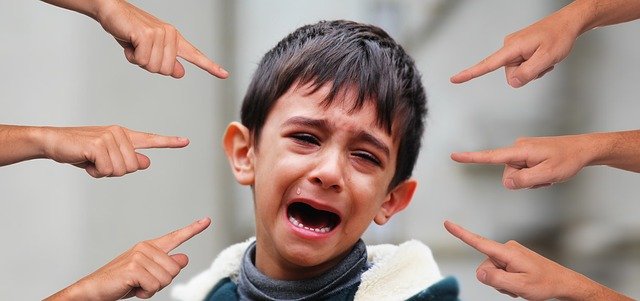

In 2017, fast food giant Burger King conducted a social experiment to demonstrate how people often refuse to speak out against bullies. The video posted on Youtube (Burger King Corporation, 2017) sought to determine whether people would respond favorably for a victim of bullying or to their meal intentionally damaged by the experimenters. Actors (high schoolers) were hired to play the roles of victim and bully in the middle of a busy store. Whoppers on the other hand were smashed into pieces by employees before wrapping them up and handing them out as orders to customers. The idea was to compare which act received more complaints. The study claimed that 95% of the customers reported their damaged Whopper but only a staggering 30% stood up to do something about the bullying.

Two directly associated phenomena were observed in this experiment: bullying and the bystander effect. Bullying has become so rampant and widespread that it has become a subject of numerous researches, dissertations and discussions worldwide. What is more intriguing and perhaps of equal importance at least in how it is linked with the perpetration of violence is the tendency of onlookers, in the presence of other bystanders, to remain disengaged and hesitate to stand up against bullies, in this case opting to care more about their smashed burgers than to stand up for a youngster about to get ‘smashed’ by bullies.

In this paper, I will attempt to present, through a review of literatures, a thorough look on these two interconnected phenomena with a view of understanding why they happen. At the end of this paper, I will proffer a few recommendations based on what experts themselves believe in helping prevent bullying by tapping on bystanders and turning their role from simply being ‘disengaged onlookers’ into something more potently positive.

Beyond smashed burgers: Bullying, its prevalence and definition

In the Philippines, a study in 2008 conducted for Plan International by the Philippine Women’s University School of Social Work revealed that bullying or abuse is experienced by one in two Filipino school children (Reyes, 2014). The study added that most of the incidents go unreported due to victims’ fear of retribution. Bullies may abuse their victims verbally, physically, or psychologically. Specifically, bullying include being made fun of or being called names, left out of activities by others, and made to do things the student did not want to (Ancho & Park, 2013). It may also involve pushing or hitting, or preventing an individual from joining a social group or participating in an activity. It may also involve harassing, embarrassing, or threatening a person using cell phones, text-messaging devices, interactive games, instant messages, or websites (cyberbullying) (Funk and Wagnalls, 2016).

The negative effects of bullying on the students’ wellbeing and its increasing prevalence prompted the Department of Education to issue Department Order No. 40 s. 2012 entitled DepEd Child Protection Policy, requiring all elementary and secondary high school in the country to set up a system that will address bullying, discrimination and other forms of violence committed within the school. In 2013, the Philippine Congress enacted Republic Act 10627 commonly known as the Anti-Bullying Law of 2013.

But what is bullying in the first place? Aside from enumerating specific examples, how is it defined and what sets it apart from other forms of aggression such as child abuse or simply teasing? To begin with, I agree with what Benitez and Justicia (2006) noted when it comes to defining the term – bullying indeed is no small task, especially if we seek a definition which is agreed on among researchers of the phenomenon. Randall (1997) categorically claimed that agreed definitions of bullying do not exist. For this purpose I have considered six related studies and one legal document for a comparative definition of bullying (see Table 1).

Table 1. A comparative description of Bullying

| Reference | Description |

| Randall, 1997 | Bullying is the aggressive behavior arising from the deliberated intent to cause physical or psychological distress to others. |

| Benitez & Justicia, 2006 | Bullying is the set of physical and/or verbal behaviors that a person or group of persons directs against a peer, in hostile, repetitive and ongoing fashion, abusing real or fictitious power, with the intent to cause harm to the victim. |

| Olweus, 2010 | An intentional repeated negative (unpleasant or hurtful) behavior by one or more persons directed against a person who has difficulty defending himself or herself. |

| RA 10627 or Anti Bullying Act of 2013 | “…any severe or repeated use by one or more students of a written, verbal or electronic expression, or a physical act of gesture, or any combination thereof, directed at another student that has the effect of actually causing or placing the latter in reasonable fear of physical or emotional harm or damage to his property, creating a hostile environment at school for the other student; infringing on the rights of the other student at school; or matetrially and substantially disrupting the education process or the orderly operation of a school.” |

| Coloroso, 2015 | Bullying is a conscious, willful and deliberate hostile activity intended to do harm. |

| Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2016 | Bullying is the repeated use of aggression by one or more people against another person or group. Bullying usually involves an imbalance in power, in which the bully is bigger or stronger, or holds a higher position than his or her target. |

| Center for Disease Control, 2016 | Bullying is a form of youth violence. CDC defines bullying as any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. Bullying may inflict harm or distress on the targeted youth including physical, psychological, social, or educational harm. |

Taking a closer look at how these references defined bullying, one could identify common themes on how bullying is determined. These can be summarized into four elements: Aggression, intent, repetition and power imbalance. Of the seven, four of the references satisfied (i.e. their definitions implied) all four elements, namely Olweus, CDC, Coloroso, and Benitez & Justicia. It could be noted that the most commonly used definition of bullying actually is from Dan Olweus who is considered the pioneer in bullying research (Dake, Price, & Telljohan, 2003). It is true in most of the researches about bullying that I have considered in this paper. Benitez and & Justicia’s (2006) definition was actually a synthesis of Olweus definition which has gone a number of revisions through time beginning in 1986 until 2010. Olweus definition cited in this paper is based on his recently updated work on bullying in (Olweus, 2010). There was no indication however whether CDC employed the works of Olweus as one of their references although it is highly likely that their definition was indeed influenced by it.

Barbara Coloroso, a parenting and anti-bullying expert, unassumingly defined bullying as a conscious, willful and deliberate hostile activity intended to do harm. At a first glance it seemed vague had she not qualified the elements of her definition. In her book (Coloroso, 2015) , an excerpt of which is made available online in a form of a handout, she enumerated four markers of bullying: imbalance of power, intent to harm, threat of further aggression, and when bullying unabated-terror. Her theory was also based largely on the works of Olweus particularly the bullying circle.

In his book on Adult bullying, Randall (1997) on the other hand, contended that aggressive behavior does not have to be regular or repeated for it to be considered a bullying behavior. He cited the case of a nurse, an incident which occurred only once but clearly was for him a case of bullying. Others would argue, Randall suggests that the fear of repeated aggression and not necessarily the actual repetition of the incident accounts for that ‘repetition element’, but for him, that fear of repeated aggression is “more a characteristic of the victim and their understanding of bullies’ personalities than of the behavior itself” (p5).

Funk and Wagnalls offers a lexical definition which is consistent with the previous and prevailing definitions. What the Philippine congress provided as a definition for enacting the anti-bullying law, although, for me is consistent with the Olweus tradition, is specifically operationalized so that it is narrowly applicable to the school setting, wherein the socio-pscyhological dimension of power imbalance in this case is not necessary for an aggression to qualify as bullying.

Nonetheless, despite the many proposed definitions, I can affirm the four major components earlier noted that permeate them all so that I find it now superfluous to create my own definition when Olweus’ definition seems sufficient. Bullying therefore is an intentional repeated negative (unpleasant or hurtful) behavior by one or more persons directed against a person who has difficulty defending himself or herself. Bullying is different from mere teasing which could either be positive or negative (Pepler & Craig, 2014) .

Being now able to adopt a definition that is well accepted among researchers and practitioners, we are lead into considering how serious can bullying be particularly for those persons tagged as having difficulty defending themselves?

Why bullying is such a “whopper”: The negative effects of bullying

Deliberately smashed burgers may still be eaten without posing any danger to a person even to the squeamish, but the ill effects of bullying to a person regardless of his/her participation are a well-documented fact.

For instance, the US Center for Disease Control, concerned on its negative effect on public health due to its prevalence in public schools stated that bullying can result in physical injury, social and emotional distress, and even death. Victimized youth are at increased risk for depression, anxiety, sleep difficulties, and poor school adjustment. Youth who bully others are at increased risk for substance use, academic problems, and violence later in adolescence and adulthood. Compared to youth who only bully, or who are only victims, bully-victims suffer the most serious consequences and are at greater risk for both mental health and behavior problems (Center for Disease Control, 2016).

A study done by the University of South Australia reported the harms done by bullying. Among bullied students who were surveyed, approximately 55% reported being made sad; 50% frightened; 45% upset; and 20% angry. Absenteeism due to bullying among bullied students was reported in the study by both students (25% of those bullied) and by the parents (30%). Student data also suggests that approximately one third of those bullied believed their capacity to do their schoolwork well had been negatively affected. According to one educational leader, the report claims, the extreme impact of bullying may extend to a large number of students who do not report being bullied (Rigby & Johnson, 2016).

Citing researches from British psychiatrists on the effects of childhood bullying beyond early childhood, Reyes said that its impact was ‘persistent and pervasive’, with people who were bullied when young more likely to have poorer cognitive functioning at age 50 (Reyes, 2014). Beyazit et al. noted what scholars suggest that cyberbullying can harm the psychological well-being of victims by leading to conflicts in their social relationships, low self-esteem, social anxiety, loneliness, disappointment, somatization, sadness, fear, rage, psychoticism, enmity, and stress, as well as leading to an increased propensity for committing crime, to illegal drug use, and to thoughts of suicide (Beyazit, Simsek, & Ayhan, 2017). This finding is confirmed in the study by Seixas, Coelho & Fischer (2013 ) which offer further evidence that those children who were involved in bullying behaviors experienced greater adjustment difficulties than their not involved counterparts.

Olweus provided a comprehensive description of the characteristics of bullies and victims and indicated that students who are bullied may develop physical symptoms such as headaches, stomach pains, or sleeping problems. They may be afraid to go to school, go to the bathroom, or ride the school bus. They may also lose interest in school, have trouble concentrating and do poorly academically. Bullied students typically lose confidence in themselves and start to think of themselves as stupid, a failure, or unattractive (Hazelden Foundation , 2007).

Given these facts, one may ask: what motivates people to engage into bullying?

An overview of why people bully

According to Fluke (2016), bullying does not arise from any single factor but is rather a complex, social process. There is, however, a considerable reliance by researchers on the social-ecological theory of Bronfenbrenner in explaining the factors that cause bullying. Bronfenbrenner, according to Fluke posits that children exist within a series of interconnected, nested environmental structures. He believes that development and behavior arise both from interactions between the child and these structures as well as interactions between the structures themselves. An important implication of the social-ecological model is that examining both variables within child and the broader ecological context is important in understanding the bullying dynamic (Fluke, 2016). The same explanation was proposed by Randall (1997) who pointed on the roots of aggressive behavior to the pre-school years brought about by a rejecting parenting style, insecure attachment, and aggressive parenting styles. He also noted the need to investigate high risk environments beyond family background.

In the traditional Olweusian view, personality characteristics or typical reaction patterns, in combination with physical strength or weakness in the case of boys, are important factors for the development of bullying problems in individual students. At the same time, environmental factors such as the attitudes, routines, and behavior of relevant adults—in particular teachers and principals—play a major role in determining the extent to which the problems will manifest themselves in a larger unit such as a classroom or a school. The attitudes and behavior of relevant peers as revealed in group processes and mechanisms are certainly also important (Hazelden Foundation , 2007). No doubt parenting plays a great part in developing a child bully or even victim.

So where’s the other 70%?

Recalling the Burger king experiment, only 30% of the customers stood up to do something about the bullying that they were witnessing. The other 70% seem to have been inhibited from acting, but by what force?

This turns our attention on the second most important object of this paper, the bystander effect, a phenomenon that has captured the interest of many social psychologists in the study of aggression and was often associated with bullying. The bystander effect refers to the phenomenon that an individual’s likelihood of helping decreases when passive bystanders are present in a critical situation (Darley & Latane´, 1968 cited in Fischer, 2011; Hortensius & de Gelder, 2014). The bystander effect describes the general tendency for an individual bystander to become less likely to help in emergency situations in the presence of other bystanders compared to witnessing the emergency alone (Latané & Nida, 1981 cited in Fluke, 2016). This is the culprit, the inhibitory force that makes a person witnessing an incident reluctant to act, and in part explains why the other 70% in that social experiment did not do something. But what’s behind this effect?

My introduction with the bystander effect was in 2012 when I was developing a leadership training module for young people in our parish. I came to know about that sad, real-life story of a murder in Queens, New York that made it popular among researchers. In 1964, Kitty Genovese was raped and murdered in an alley while several of her neighbors looked on. No one intervened until it was too late.

Genovese’s murder, although not a case of simple bullying, epitomized that pattern of social behavior which will later be called the Genovese syndrome or bystander effect. It actually sparked the series of researches trying to understand why people would refuse to act in such incidences. Darley and Latane’s study was launched a few years after the Genovese murder case, which was followed by further meta-analyses.

Consistent with the Genovese case, the customers in that Burger King video who failed to report or at least do something about the bullying are clear examples of passive bystanders.

In the early 90s, Olweus introduced a structural model of understanding different roles in the bullying set-up which he called the bullying circle. He contended that bullies and victims naturally occupy key positions in the configuration of bully/victim problems but that other [persons] also play important roles and display different attitudes and reactions toward an acute bullying situation. The bullying circle represents the various ways in which most individuals in bully/victim problems are involved in or affected by them. Aside from the Bully and the victim there are followers/henchmen, passive bullies, passive supporters, disengaged onlookers, possible defender and defender of the victim (Olweus 2001, cited in Olweus 2010).

Disengaged onlookers and possible defenders are both bystanders who, as Fluke (2016) reported, are present in the vast majority of bullying situations and are potential sources of help. This is supported by the work of Barbara Coloroso who argued that while bystanders abet bullying by their commission and omission, they could nevertheless turn into a potent force of averting bullying once they learn to stand up for their peers and become active witnesses (Coloroso, 2015).

Coloroso was among those who specifically discussed at length the particular role of bystanders in the circle of bullying. She offered some possible explanations on why people choose not to act in these instances. Bystanders according to Coloroso are: afraid of getting hurt themselves, afraid of becoming the new target for the bully, feeling that by intervening they will only make the situation worse, and lastly, clueless of what to do.

For Fluke (2016), when bystanders choose to intervene on behalf of the victim, they are able to stop the bullying about 50% of the time. Unfortunately, bystanders rarely stand up for victims, instead frequently choosing to help the perpetrator or passively observe the bullying situation. A person who finds him or herself witnessing an emergency alone will often decide to help the person in need; yet surround that same person with others who witness the same event, and that person becomes far less likely to lend a helping hand (citing Latané & Nida, 1981).

Hortensius & de Gelder (2014) provides a biological point of view in understanding bullying by studying underlying neural mechanisms involved. They investigated the neurofunctional basis of group influences on individual helping behavior using videos depicting the scene of an emergency manipulating the presence and group size of other persons at the scene. Without knowing the contents of the videos, the participants were asked to perform a color detection task that was “unrelated to the stimulus conditions and did not require cognitive involvement, or recognition or understanding of the situation”. The results provide insight in the neural mechanisms of the bystander effect, although not in a causal effect. In layman’s term, there was something about seeing other people present in the same situation which reduces the individual’s spontaneous tendency to help. The more witnesses are present the less helpful one could be.

To account for the effect, Fischer cites the five-step psychological process model based on the works of Latane´ and Darley. It was postulated that for intervention to occur, the bystander needs to (1) notice a critical situation, (2) construe the situation as an emergency, (3) develop a feeling of personal responsibility, (4) believe that he or she has the skills necessary to succeed, and (5) reach a conscious decision to help. Moreover, according to the same theory there are three different psychological processes that might interfere with the completion of this sequence. The first process is diffusion of responsibility, which refers to the tendency to subjectively divide the personal responsibility to help by the number (N) of bystanders. The second process is evaluation apprehension, which refers to the fear of being judged by others when acting publicly. The third process is pluralistic ignorance, which results from the tendency to rely on the overt reactions of others when defining an ambiguous situation (Fischer, et al., 2011). It is normal, I would affirm for a person to think first before acting in situations where he/she could possibly get into trouble.

Thankfully, bystander effects are not always as negative as they are typically portrayed. We take for example the research by van Bommel and his colleagues (van Bommel, van Prooijen, Ellfers, & Van Lange, 2012) which provides for the needed breathing space in the suffocating bystander effect trend. Their study demonstrates that the presence of others can have exceptionally fruitful effects in curbing bullying citing the principle of self-awareness and reputational reward (cost-reward model of helping behavior). This theory suggests that the presence of bystanders can actually increase helping behavior, notably in situations where public self-awareness is increased through the use of accountability cues such as cameras. This specific condition appears in contrast with the traditional understanding of the phenomenon as cited by Fischer.

In the same vein, Fluke’s (2016) findings reveal that people who are aware of the ‘reputational costs and rewards’ of their behavior become motivated by concerns of what others may think. In this way, a bystander may help a victim when they are aware that doing so will advance their reputation (people will think good about them). His study specifically identified particularly dangerous or unambiguous bullying situations (i.e., physical bullying) as cases that will most likely increase likelihood of help being provided as compared to a non-emergency case such as verbal bullying.

Reversing the bystander effect to reduce bullying

We do not fall short on the many intervention programs for preventing bullying; with the bystander effect on the other hand, further researches and meta-analyses are needed. Nevertheless, the preceding processes and principles described by experts as a result of years of studies are vital in the understanding of this phenomenon if we are to aim the reversal of its effect in the hope that bystanders are enabled to make this conscious decision of giving help to those who need them at the right moment.

This gives us the courage to assert that bullying and bystander effect, no matter how monstrous tandem they seem, are not ‘incurable’. There is much we can do to reverse the bystander effect to reduce bullying.

For Coloroso, the key to effective intervention for bullying prevention is summarized in her ‘3 Ps’ recommendation: policy, procedures, program. She suggests that policies must always include a sanction against bullying. Procedures, on the other hand, for restorative justice must be tailored to the unique problems and possible solutions required to repair the damage done through bullying. Programs, finally must address what bullying is; how it impacts students; what students are to do if they are targeted or if they are aware of another student being targeted. What is needed is a comprehensive school-led/community-based approach she added. Coloroso argues that bullying is challenged when the majority stands up against cruel acts of minority. Here she identified as a potent force kids themselves who show bullies that their cruel behavior will not be tolerated. In this case they can become active witnesses standing up for their peers, speaking out against injustice and taking responsibility for what happened among themselves. How to encourage kids to do so is the next rational question.

The answer may be found in what Pepler & Craig (2014) proposed as a whole school approach and expanded in what Brewer (2017) cited as the whole school, whole community, whole child approach (WSCC). Said approach brings everyone together to work toward creating a safe, inclusive, and accepting school where bullying problems are prevented and handled effectively when they arise. A whole school approach involves the administration, teaching and school staff, children, youth, parents/guardians, and the broader community. However such an approach is difficult to achieve if there are disagreements between staff members on key issues as noted by Rigby & Johnson (2016).

In this approach, children and youth who witness bullying can be coached to become “upstanders” by learning: (1) the ways that their behavior contributes to the bullying problem (e.g., attention, reinforcement, joining in, ignoring the plight of the victimized child or youth) (2) the importance of reporting bullying when someone is not safe, and (3) to support vulnerable peers (Coloroso, 2015). Further steps schools might take to reduce bullying, and proposed by Rigby & Johnson (2016), include among others, better trainings within schools, including teachers, students, parents, and the community as a whole.

If we are to take the van Bommel’s and Fluke’s recommendations, we can incorporate in this approach the principles of ‘self-awareness’ and ‘reputational benefits’. CCTV cameras may be installed and children made aware of them which could deter violence and following public self-awareness principles may encourage would bystanders to stand up for victims and against bullies when needed. Policies could also include providing recognition or incentives to people, children and adults alike, who help address bullying or at least report it.

These tasks understandably are never easy but with the WSCC model, kids could be provided a safer environment that encourages them to always act courageously when situation warrants it and at the same time would not endanger ‘upstanders’ themselves.

A decent review of bullying reduction programs should not miss the Olweus bullying prevention program which according to Eriksen et al., (Eriksen, Nielsen, & Simonsen, 2012) underlies bullying prevention programs implemented all over the world. The idea is to combine warmth and positive involvement from adults with firm limits to unacceptable behavior. Violation of the limits and rules should be followed by non-hostile, non-physical sanctions. This program implicitly requires some monitoring of behavior as well as adults acting as authorities at least in some respects.

Conclusion

Undeniably, bullying is a persistent, prevalent and serious social problem and it is true in almost all cultures. The magnitude of evidences based on researches allows the development of well-informed measures and programs that could help rationally address bullying. Although a majority of bullying incidences happens in schools and a variety of factors increase bullying in that setting, it should be emphasized that bullying happens in all spheres of social interaction (just like in a burger chain) and is influenced by a complex social process. Prevention therefore is incumbent upon a whole school, whole community approach which promotes inclusive interventions that go beyond the school gates.

In schools and in society in general, culturally-responsive interventions (e.g. curriculum, community program, advocacies) that foster the development of respect and appreciation for all persons are needed. Sanctions should also promote non-violent actions; such is the direction the Department of Education has recently pursued with the introduction of ‘positive discipline’ measures. The presence of an anti-bullying law in the country is part of the ‘policy’ measure encouraged by experts, and reflects the whole community approach. Stakeholders should nonethelesslook beyond legislations, giving more prime to evidence-based approaches.

There is indeed a great and potent role bystanders play in helping reduce and prevent bullying and this is contingent on promoting a safe environment that could incite helping behavior in individuals even in the presence of more passive witnesses and without them fearing possible retribution.

Moreover, understanding the influence of the bystander effect in the bullying configuration, which is the object and limit of this paper, allows for the development of well-informed measures and programs. Further researches on this area are encouraged particularly on how it could be reversed, a perspective which shows promising trend.

By this time, I think I can eat my burger.

References

Ancho, I. V., & Park, S. (2013). School Violence in the Philippines: A case study on program and policies. Advance Science and Technology Letters (Education), 36, 27-31.

Benitez, J., & Justicia, F. (2006). Bullying: description and analysis of the phenomenon. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 4 (2)(9), 151-170.

Beyazit, U., Simsek, S., & Ayhan, A. (2017). An examination of predictve factors of cyberbullying in adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality, 45(9), 1511-1522.

Brewer, S. (2017, Fall). Addressing Youth Bullying through the whole child model. Education, 138(1), 42-46.

Burger King Corporation. (2017, October 17). Bullying Jr. Retrieved October 28, 2017, from https://youtu.be/mnKPEsbTo9s

Center for Disease Control. (2016). Understanding bullying factsheet. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from http://www.cdc.gov: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/bullying-definitions-final-a.pdf.

Coloroso, B. (2015). The bully, bullied and the not so innocent bystander. Retrieved November 4, 2017, from http://www.kidsareworthit.com.

Dake, J., Price, J., & Telljohan, S. (2003). The nature and extent of bullying at school. Journal of School Health, 73(5), 173-180.

Eriksen, T., Nielsen, H., & Simonsen, M. (2012). The Effects of bullying in elementary school. Bonn, Germany: IZA.

Fischer, P., Krueger, J., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmuller Andreas, Frey, D., . . . Kainbacher, M. (2011). The Bystander effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 517-537.

Fluke, S. M. (2016). Standing up or standing by:Examining the bystander effect in school bullying. Public Access Theses and Dissertations from the College of Education and Human Sciences, 266.

Funk and Wagnalls. (2016). Funk and Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia. Chicago: World Book Incorporated.

Hazelden Foundation . (2007). Recognizing the many faces of bullying.

Hortensius, R., & de Gelder, B. (2014). The neural basis of the bystander effect- the influence of group size on neural activity when witnessing an emergency. NeuroImage, 53-58.

Olweus, D. (2010, January). Bullying in Schools: facts and intervention. Retrieved November 4, 2017, from http://www.researchgate.net: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/228654357_Bullying_in_schools_facts_and_intervention

Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (2014). Bullying prevention and intervention in the school environment. Retrieved November 5, 2017, from http://www.prevnet.ca: http://www.prevnet.ca/sites/prevnet.ca/files/prevnet_facts_and_tools_for_schools.pdf

Randall, P. (1997). Adult Bullying: perpetrators and victims. London: Routledge.

Reyes, T. M. (2014, June 10). Bullying: A parent’s guide to fighting back. Retrieved November 3, 2017, from Phillippine Council for Health Research and Development: http://www.pchrd.dost.gov.ph

Rigby, K., & Johnson, K. (2016). The prevalence and effectiveness of anti-bullying strategies employed in Australian schools. Adelaide: University of South Australia.

Seixas, S., Coelho, J., & Nicolas-Fisher, G. (2013 ). Bullies, victims and Bully victims: Impact on health profile. Educacao, Sociedade & Culturas, 53-75.

van Bommel, M., van Prooijen, J., Ellfers, H., & Van Lange, P. (2012). Be aware to care: Public self-awareness leads to a reversal of the bystander effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Elsevier Inc.